No urban achievements without agricultural achievements (13 May 2012). Let’s take a closer look at the civilizations of the Egyptians, Maya, Greek, Romans, Asians and Europeans, and see how they managed to feed their many cities.

Egypt

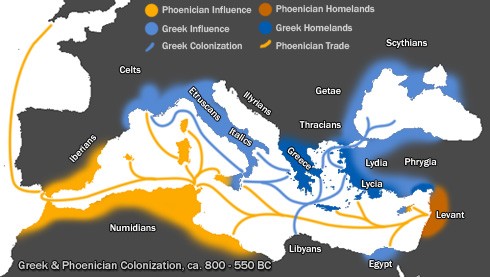

Few peoples on earth could so easily build a stable and prosperous life as the ancient Egyptians. Imagine this river Nile, flowing calmly through the deserts of Egypt, flooding its shores every year in a fairly predictable way. If you need to travel north, float along. If you need to travel south, take a sailing ship and the trade wind will push you along. Every time the river floods, in August and September, it waters the shores and leaves behind fertile soil (silt) from the Ethiopian Highlands.The only thing you might want to do is lead the water into basins so that it can stay a bit longer than it would have naturally stayed, allowing the earth to become fully saturated for later planting. You might also want to use these basins to lead the water away from cities and gardens. After the flood, in October, you can then start planting your grains, vegetables and fruits.

This is what the Egyptians did. And it is quite an ironic fact that Egypt is nowadays the world’s biggest wheat importer, for with the abundance of wheat they produced in the last 5,000 years, they not only built an impressive civilization themselves, they also played an important role in enabling later civilizations to feed their urbanites. Rome, for example, could only prosper with a lot of wheat from Egypt (21 December 2012).

Fame starts with a lot of food in history. And few kings in history could so easily control and take advantage of their people’s food production as the pharaohs (starting with Menes around 3100 BC). Imagine all your subjects living in villages and cities on the shores of one river, producing an abundant amount of wheat and using the one Nile to exchange goods and build a rich culture. The only thing you need to do as pharaoh, is to control that one river and make sure that part of the food and goods is heading your way every now and then. Fast desserts form a natural protection against invasions of massive armies, so you don’t need to spend a lot of your income on maintaining an army of soldiers. What will you do with your wealth? How about feeding an army of workers to build a pyramid?

Maya

The Maya are also known for their awe-inspiring pyramids, but unlike the Egyptians they had to cope with tough environmental conditions by developing ingenious methods to grow crops in jungle and wetland areas. The Maya civilization first emerged sometime before 1000 BC and reached its peak in the “Classic Period”, between 250 and 900 AD. In this last period, millions of people lived in cities with tens of thousands of urbanites on the Yucatán Peninsula in current Mexico and Guatemala, making it one the most densely populated areas in the world. There are no rivers in this area, so how on earth did they feed the urbanites?

Many of the cities in Yucatán were built around cenotes, being their only permanent source of water. A cenote is a deep natural pit, or sinkhole, that exposes groundwater underneath. The sacred cenote of Chichén Itzá was by far the most important one. The rain god Chaac was thought to live at the bottom of it. Many humans were sacrificed to appease him, especially young males, presumably because they represented strength and power. Where the Maya couldn’t rely on cenotes, they built cisterns to catch and store rainwater.

Then there was the impressive way the Maya managed to produce a healthy diet of different crops in the midst of jungles and swamps. In his book “1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus” (2005, p. 197), Charles C. Mann describes the milpa agriculture of the Maya as follows:

A milpa is a field, usually but not always recently cleared, in which farmers plant a dozen crops at once including maize, avocados, multiple varieties of squash and bean, melon, tomatoes, chilis, sweet potato, jícama, amaranth, and mucana. (..) Milpa crops are nutritionally and environmentally complementary. Maize lacks the amino acids lysine and tryptophan, with which the body needs to make proteins and niacin (..). Beans have both lysine and tryptophan. (..) Squashes, for their part, provide an array of vitamins; avocados, fats. The milpa, in the estimation of H. Garrison Wilkes, a maize researcher at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, “is one of the most successful human inventions ever created“.

Corn (or maize) was the most important and sacred crop of all. For every detail of planting, sowing, and harvesting there was a ritual. These rituals not only turned farming into a highly social and spiritual event, they also ensured that the cultivation of corn was done at the right moment and in the right way, from generation to generation.

Equally revered by the Maya was a drink worth more than gold: chocolate. It took no less than 3000 years after its first discovery by the Indians, before it started to seduce and comfort the rest of the world.

BACK TO BLOGS