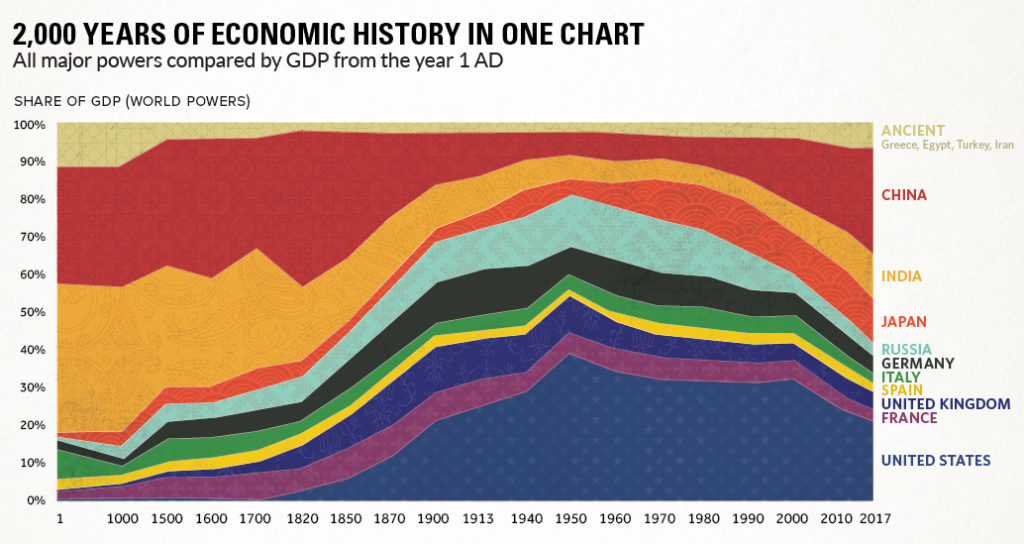

Five centuries of western domination are currently being replaced by a new world order. All the political, economic, military, cultural and ideological cards are already being reshuffled. If the Corona virus rages deep enough, it will ‘only’ catalyze this transition. In this essay, I try to briefly describe three of these major intersections in our time. Part 3: Social competition / Part 1. Ideological / Part 2. ‘Glocal’

The third question, begging for attention in this transition time and even more so in our corona time, is the tremendous difference in vulnerability between people in one society. I don’t mean here the increased vulnerability of elderly people, but the vulnerability of people lacking opportunities and securities.

In the past years many have pointed to the growing inequality in the world, particularly in ‘undercover oligarchies’ like China, Russia, India, Brazil and the US. Europe, Canada and Australia are in a better shape because of a more extensive welfare system, a stronger social dialogue, and a levelling tax system. But also in these parts of the world we see a growing vulnerability in society as a result of people not being able to escape their inadequate circumstances. And also in these countries, this can be the result of mechanisms that make people lack even the opportunity to flourish.

Consider the growing number of self-employed workers and flex workers who struggle due to temporary jobs, low incomes, little social security and no political voice. In 2011, Guy Standing wrote a book about this group with the title The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. (Precariat is a combination of ‘precarious’ en ‘proletariat’.) Standing warns that chronic vulnerability makes people prone to populism and extremism.

In The Meritocracy Trap (2019), Daniel Markovits describes how a group of American citizens, who first benefitted from a meritocratic society to climb the social ladder, is now forming a closed caste at the top that is hardly accessible for outsiders. The result is a split society with on the one hand an elite that, from an early age on, prepares itself for top positions with top salaries and top responsibilities, and on the other hand a ‘precariat’ that lacks the means to keep up with the elite and is therefore condemned to insecure implementation work. For those who wish to know what this looks like, Markovits refers to the world’s largest taxi company Uber: at the top a small group of privileged and very rich designers and managers, at the bottom millions of underpaid and overworked drivers who will never be able to work themselves up to the level of the first group.

Also in Europe, Australia and Canada, although not as dramatic as in the US, social mobility is dropping rapidly and many are only one accident away from big financial trouble. And we don’t even know yet, how automation, robotics and digitalisation will disrupt the global labour market in the years to come. With new urgency we are confronted with an old question: how to avoid social disruption because of structural inequality?

Now look at the pandemic the world is facing, in the midst of this social competition. The good news is that we suddenly have an eye for people who were so easily overlooked in the past: all the people whose essential work keeps the heart of society running. At the same time, our world is facing a solidarity test with hardly any precedent in history.

I don’t need to describe the misery as a result of the many lockdowns in the world. For millions of owners, losing their business means the end of a life dream and sleepless nights over every layoff. For 60% of US citizens, no work means no health insurance. For millions of factory workers, no global trade means no living. For millions of labour migrants, no income abroad means no family support at home. And for millions of day labourers, no work for a day means no food for a day.

With fear and trembling the world awaits the social and economic damage when the dust of corona settles. Yet one thing is clear already: people who have nothing to lose are prone to extreme ‘solutions’: to communist revolutions, ethnic cleansing, fascist nationalism, scapegoating and sectarian violence. We saw it a century ago, and again these are real threats.

Anger can easily shape these threats, for nothing angers humans more than a lack of recognition. What we cannot afford in times of growing uncertainty is people also feeling humiliated by ending not only economically but also socially (in terms of appreciation and respect) at the bottom of society. If we want to avoid the anger this causes, we need to ask ourselves with new urgency: how to secure each person’s self-esteem and dignity?

In many countries this will provoke another question, namely what is more important to us: the income someone generates, or someone’s contribution to keeping society running? As long as we stress the first, society will continue to be divided into ‘workers’ and ‘volunteers’, with the last group feeling easily that they are somehow falling short. If we stress the second, we will be able to appreciate anyone for anything that contributes to the common good: not only the police officer, the accountant or the nurse, but also the family care giver, the church elder or the baby-sitting granny.

Such a generous appreciation might not be easy. It may be tempting to think that all this ‘volunteer work’ is still made possible by those with ‘a decent job’. In order to fully appreciate ‘unpaid work’, we may need to calculate its economic value (for example the costs that are saved on the health care system thanks to the dedication of family caregivers). The next question will be, how much value we want to attach to the different contributions in society, and to what extent we want to ensure all contributions are somehow financially ‘recognised and appreciated’.

Hopefully, corona is encouraging us to be less fascinated by CEO’s and financial traders and more impressed by the silent forces and forgotten callings that we are surrounded by. In times like these, when unemployment is skyrocketing and the already vulnerable are being hit the hardest, we cannot afford to lose sight of what everyone can still contribute to the common good – in whatever valuable way. For people do not only want to be loved, they also want to be needed. More than charity, we need a solidarity that takes the shape of a commitment to acknowledge and include each and everyone’s qualities.

These are no optional exercises. The solidarity test that we face will in many cases turn out to be a matter of anger prevention. And what applies to societies, is just as relevant at the international level: how to avoid that entire nations have nothing to lose and become prone to extreme ‘solutions’?

The answer to this last question requires no less than a world vision. Time to rise above the election rhetoric of four-year plans and reflect on what we want our nations and world to look like in 2030, 2040, 2050, and what investments this requires today. Climate change is already forcing us to think this way, but there are many other areas (mentioned above) in which we have no choice but to chase a joint vision. Jeffrey Sachs writes in Common Wealth (2008): “The defining challenge of the 21st century will be to face the reality that humanity shares a common fate on a crowded planet.” That is the way things are. And time is short. Corona catalyses what is moving already.