If you have a spare hour, enjoy the video below in which I take you around the globe, summarizing the major positive and negative trends in today’s world. In 2018, I held this lecture for senior leaders of major corporations in Sydney and Melbourne (companies like Perpetual Limited, QBE, Deloitte, Karrikins Group, Oxford University Press, Worley Parsons and Pearson) in my role as Chief of Vision within World Vision Australia. This video was recorded by QBE in Sydney.

Three facts that defy our traditional perception of the world

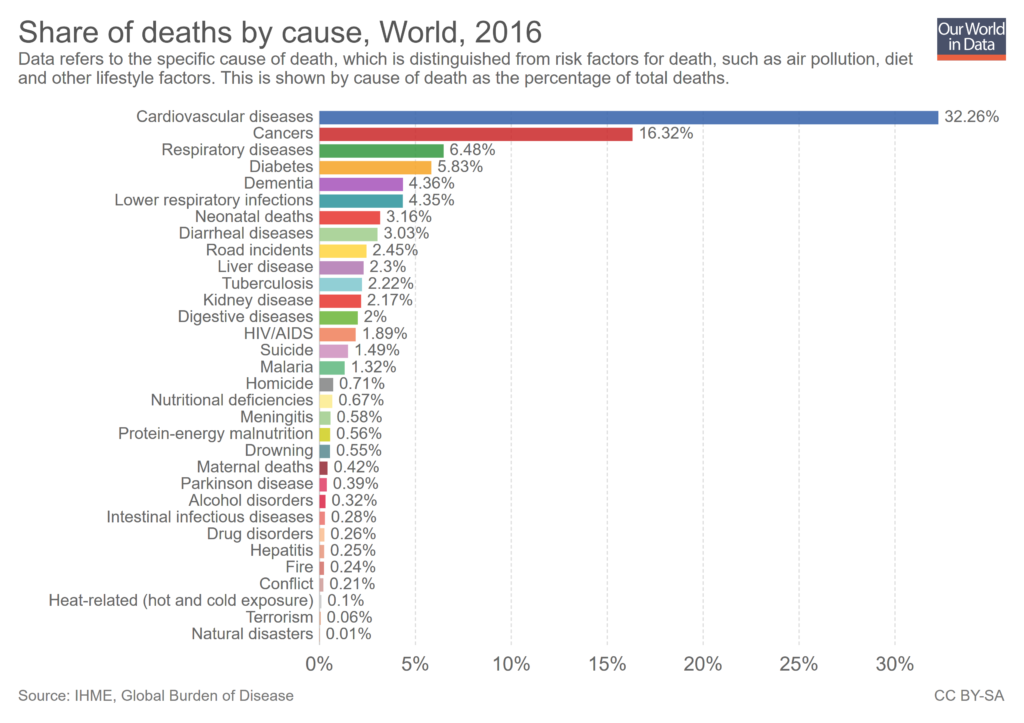

Based on millennia of misery, one would assume that most of the fatalities in the world are caused by hunger, infectious diseases or violence. In reality, however, we have entered quite a different world. Today…

more people die from eating too much than from eating too little,

more people die of old age than of infectious diseases,

more people commit suicide than are killed by soldiers, terrorists or criminals.

So, to many people out there: take care of yourself, for you are now the biggest risk in your life!

Europe has a simple choice: be the world’s 4th giant or a bunch of glorious dwarfs

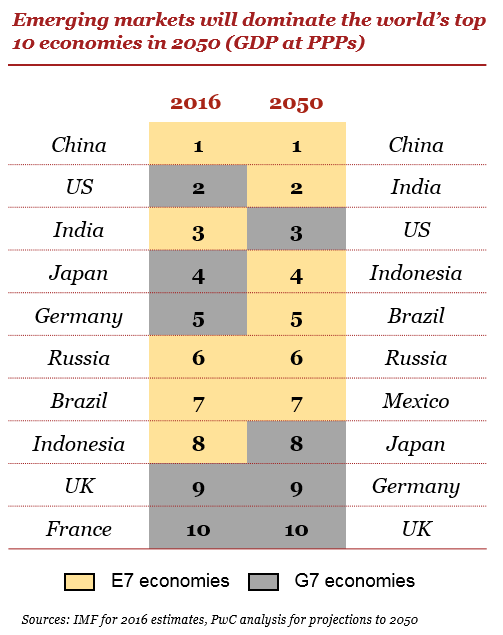

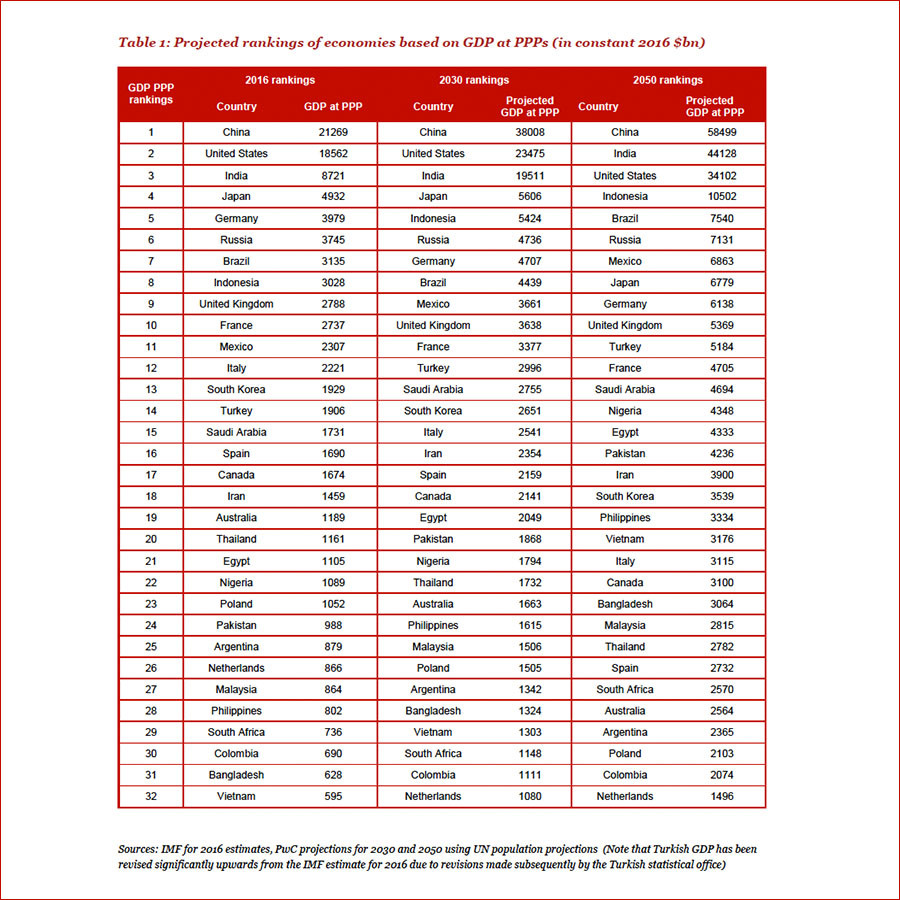

If the GDP projections of PwC are correct, not a single European country will sit at the table when the G8 gathers in 2050. Germany can still join the G8 in 2030, but not the country that is currently most absorbed by defending its sovereignty: the United Kingdom.

Of course, projections like these should be taken with a substantial grain of salt. But it sends a crystal clear message to Europe: now is the time to make up your mind! What do you really want? Be the 4th giant in the world – next to China, India and the US – or settle for glorious dwarfness by prioritizing national sovereignty over European unity?

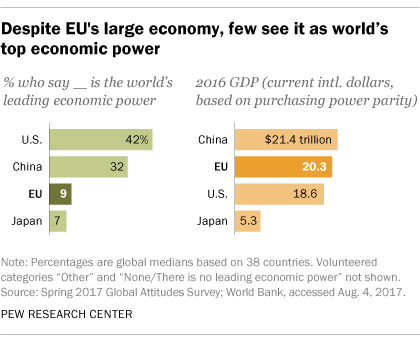

Economically, the EU is already a giant. It is the world’s second-largest economy by GDP. But as long as the EU doesn’t grow up as a political entity (with one democratically chosen leader speaking on behalf of all EU members and citizens), we will continue to see a mind-boggling contradiction t between the EU’s strength as economic power and weakness as political leader, illustrated by the survey below:

Below PwC’s ranking of the top-32 economies in 2016, 2030 en 2050. Europe is rapidly losing ground in the market place. Time to make up its mind. The current EU-approach is neither fish nor fowl, with for example a G20 containing both leaders of individual EU-countries and a representative of the EU. The more the rankings below become a reality, the more European countries will have to decide: splendid isolation as sovereign nations or significant participation as united EU.

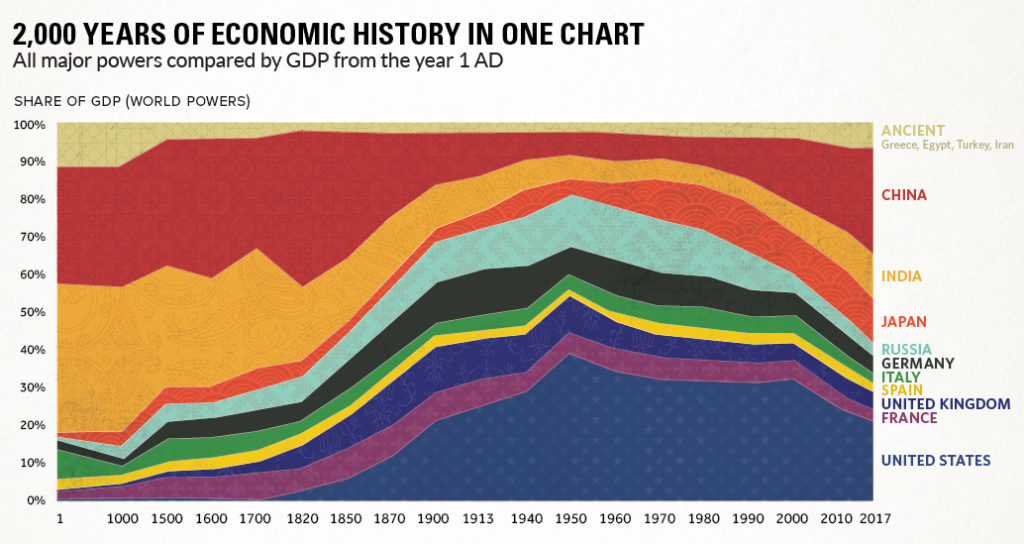

18 of the last 20 centuries China and India were the biggest economies

A quick look at the above chart and you may be surprised to see that China and India were by far the biggest economies in the first 18 of the last 20 centuries. Sure, it is all based on estimations and using different time intervals on the x-axis is actually not done. But nevertheless, we can draw some valuable insights from this chart.

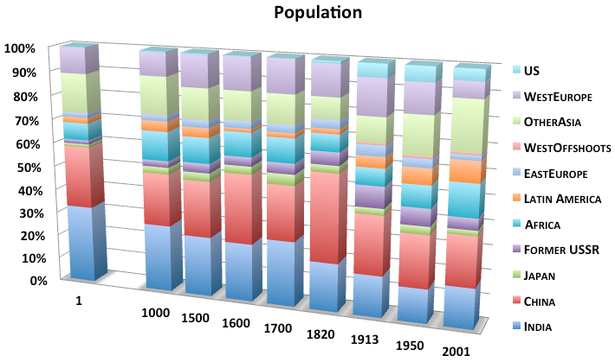

Until 1800, economic progress was largely linear and linked to population growth. The more people, the bigger the share of GDP in the global economy. Hence the leading position of China and India. Already 2000 years ago, 60% of the world’s population lived in these two countries (thanks to a growing amount of tea, cotton and rice).

But then the Industrial Revolution changed the game altogether: suddenly, productivity started determining a country’s share of GDP in the world’s economy. Europe and the United States could produce way more wealth with their factories than the size of their population would indicate. It gave them a head start in economic power, which they unashamedly translated into military power. China and India faced severe humiliations from the West in the last 2 centuries.

But things are changing dramatically again. China and India are catching up, with China behaving like a petrol engine and India like a diesel engine (needing more time to warm up). The leverage of the West is diminishing, their head start disappearing. And this time, China and India can combine their industrial power with their immense population. Once both countries are ‘up to date’ and ‘up to scale’, their huge work force and internal market will allow them to go above and beyond. China may have reached this point already, India is on its way.

Once all of the catching up is done, we will see an economic world order that shouldn’t surprise anyone: a world order that existed already for 18 of the last 20 centuries and only got disrupted for 200 years.

Today’s biggest issue is that there are so many big issues

In August 2018 I was interviewed by Perpetual Limited, one of Australia’s major providers of financial market services. Below the 5-minute video, now available. Right after the interview, I had the privilege of speaking about the same topic – today’s global trends – to Perpetual’s top clients.

Thanks to @perpetual_ltd for a courageous conversation on the perfect storm of global trends in the world economy as narrated by Evert-Jan Ouweneel of @WorldVision. So much food for thought here pic.twitter.com/BLfSeSezhW

— WiBF (@WiBF_Aus) August 16, 2018

Resilience in times of uncertainty

In May 2017 I was interviewed by Alan Kohler, one of Australia’s most experienced and appreciated business commentators. Topic is the importance of investing in resilience and faith in the future when times are uncertain.

Transcript and charts are available on his very insightful website The Constant Investor.

Who inspires the West

As a Dutchman, visiting Australia and other Western countries regularly, it strikes me how we are all taken by the same fear and discontent. Only a few decades ago, after the fall of communism, we celebrated our First World victory with uncut triumphalism. Today, it easily feels as if we are on the losing end of history and living in a world that isn’t ‘ours’ anymore.

Not a misplaced sentiment, as until recently the world was ‘ours’ indeed. For centuries we did not hesitate to exercise our military and economic power to acquire the best deals and most lucrative businesses. The result was an unprecedented wealth and a job security we happily got used to. But things are changing. New powers are reshuffling the cards dramatically, national affairs are being overruled by global affairs, old certainties are becoming uncertain, and even democracy, this flagship of the West, is facing growing competition from authoritarian regimes.

We live in stormy times, no doubt. And this is the inevitable question in a storm: will our body or our spirit take over? Do we allow ourselves to slip into the survival mode of an animal? Or do we have the resilience to stick to the ways of a reasonable and compassionate human being?

If the latter: who will lead? And if less and less people listen to pastors, priests and politicians: who will fill the gap? You and me, perhaps?

Allow me to describe three features of the storm that is hitting us, and a few ways to take an inspiring stand in it.

Three features of the storm

For the first time in 5000 years, the whole world needs to work together to get the whole planet in order. Issues like climate change, cyber threats, terrorism, trafficking, slavery, pandemics or nuclear threats can only be solved if countries closely cooperate. This contains also some good news: reality demands that we overcome our differences. The current trend, however, is in the opposite direction towards nationalism, protectionism and xenophobia. And the only leaders who can actually fix the planet are the ones elected to defend the self-interest of their country. A group of legitimate egoists is supposed to seek the greater good. No reason (yet) to prepare for the apocalypse, but no reason for blind optimism either.

For the first time in 500 years, the West needs to share its power and wealth with the rest. Precisely when the world is reorganising itself on an unprecedented scale, the West is losing its grip on it. A most inconvenient coincidence. Western citizens call upon their leaders to restore the securities of the past. But the politicians are in an impossible position: on the one hand they are held accountable for the well-being of their nation, on the other hand this well-being is more and more dependent on issues they do not control (like climate change or the world economy). Some flex their rhetorical muscles: just close the curtains and pretend the rest of the world doesn’t count. But the issues turn out to be more obstinate than any country put first.

For the first time in 50 years, Westerners need a Grand Narrative to be resilient again. For decades we could afford abandoning all the religious and ideological perspectives that used to give us hope and consolation. For decades, the old Narratives could not offer us something better than we already had. But now, as our grip on things is loosening, we realise that we have very little to gain and so much to lose. Feelings of insecurity kick in, requiring a new resilience. And resilience is precisely what we lack in the West. Even though we are still quite able to be happy when things go well, we are the first to get anxious and depressed when things go wrong.

In the past, many would take comfort and courage from the hope for a communist revolution, others would focus on heavenly happiness in the afterlife, and still others would await the Messianic age on earth. Whatever Narrative people embraced, it gave them a joint strength to bite the bullet. In our time only one gospel dominates: “If it’s going to be, it’s up to me.” A great pep talk to get us out of bed. But it leaves us empty-handed when we cannot control our life any more. The current storm confronts us precisely with the latter. Many issues have grown too big to be solved by a single human or even a single nation. If we don’t invest in some resilience, our mental and emotional empty-handedness may turn out to be very costly (if not dangerous) for Western societies and beyond.

Seven inspiring stands

What inspires in stormy times? Not a lot of talking, but people living what they believe in. What makes their lives inspiring? Seven stands, I would say.

- Stay calm. Inspiring people have the strength to control their fear and discontent. They don’t panic or give up in a storm, but keep looking for creative and lasting solutions.

- Stay compassionate. Inspiring people are stronger than their biological self-defence mechanisms. Rather than spending all their energy on saving themselves, they have the strength to look around in a storm and care for the ones who are hit the most.

- Stay hopeful. In whatever secular or religious form, inspiring people don’t lose the ability to have faith in the future. They keep communicating in their words and actions that this world is worth investing in.

- Stay visionary. Inspiring people withstand short-sighted answers to fear and discontent. They seek the well-being of the entire planet and all nations, rather than pursuing a protection and expansion plan for their tribe only.

- Stay stubborn. Inspiring people withstand social pressure and stick to what they believe in and who they believe in. Consistency and loyalty turns them into beacons of hope and direction for others.

- Stay human. Inspiring people bridge the social gaps in society by being human among humans, regardless of religion, race, ethnicity or gender.

- Stay joyful. Inspiring people keep celebrating the good things in life. They don’t deny what is wrong, but hold on to a sense of gratitude for anyone or anything that points them to the gift of life. Fear and discontent are contagious, but inspiring people know: so is joy. Whatever the moods and whims of a nervous society, inspiring people continue to build a spirited counter-movement of hope- and compassion carriers that can take us through the storm. Who is in?

The need for religious literacy in secular societies

On 5 August 2015 I was interviewed by ABC Radio in Australia about the world becoming not less but more religious, making it important for people in secular societies to raise their ‘religious literacy’ in order to understand the rest.

Here is more on the ABC radio website.

Why tomorrow will be less democratic than today

Western-style democracy, emphasizing individual freedoms and rights, is under global pressure and facing decline even in the West. Here are five reasons why.

1. China gets away with an authoritarian approach

Some banks are “too big to fail”, some countries are “too big to franchise”. There is no way Western democracies can shape China in their own image. It is also clear by now that they are not willing to sacrifice political and economic relations with China in exchange for upholding a Western view on democracy and human rights. So, get used to a world where superpowers can be openly undemocratic (according to Western standards) and get away with it. And don’t forget how inspiring it can be for other regimes, and how much it can add legitimacy to their own authoritarian ambitions, to see China ‘win’ with an authoritarian approach.

(Russia is a different and more complicated story, due to its strong army and vulnerable economy. Its military strength demands caution in the West; its economic needs provide opportunities for the West.)

2. Western-style democracy does not seem the ultimate solution any longer

Western-style democracy is a tough seed to sow: in most countries where it was recently introduced, it failed. Democracy is a vulnerable system as it requires discussions among equals and does not stop the election of undemocratic people and parties. Whatever its value, recent history has made it much easier for opponents to dismiss it as a universal solution. In October 2014, an influential journal of the Chinese Communist Party (Qiushi) made the following statement with reference to the enduring violence and turmoil in countries like Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq and Libya:

The West always brags that its own democracy is a ‘universal value’ and denies there is any other form of democracy… Western democracy has innate internal flaws and certainly is not a ‘universal value’; its blind copying can only lead to disaster.

The days are over when the West could suffice with simply supposing the superior nature and universal resolving power of its democracy.

3. Secular societies lack the resilience to withstand their need for security

More freedom means less security, more security means less freedom. A well-known dilemma in democracies, leading to the question: what will democracies need more in the coming years, security or freedom? The answer is clearly security, for two reasons: 1) the growing amount of threats within and around democracies, making citizens feel more vulnerable, 2) a lack of resilience in democracies to accept risks.

Ad 2) The Democracy Index of The Economist Intelligence Unit shows that the most democratic countries also happen to be the most secular countries in the world. This combination seems to have a price: the less people can surrender to Someone or Something that controls the universe – a God (Jews, Muslims, Christians), Spirit or Life Force (Taoists, Buddhists, New Agers), Social Order (Confucianists, Socialists) – the more difficult it becomes to accept adversities and risks in life. Friends and family can compensate to some extent, but solitude is a major problem in secular societies and only some problems can be fixed by others. So, what we see in secular societies is a lack of resilience: people can be the happiest in the world when their life is in order, but easily get anxious or depressed when things get out of hand. There is little tolerance for anything that threatens the good life. Combine this with the growing threats in the world and we may see a growing willingness in precisely the most democratic countries, to sacrifice freedoms in exchange for more security.

Big question: where will this process end? How much loss of freedom does it take before people start to accept insecurities in exchange for freedom?

4. World issues cannot be solved in a tolerant way

Pandemics, climate change, cyber crime, international crime, global terrorism, nuclear risks – the dangers these issues contain can only be tackled if all countries cooperate. Leave one out, and hackers, criminal organizations and terrorists will pick that country as their hiding place. And so, the more urgent these issues become, the less countries will be patient with those that obstruct the process. World issues, by their nature, don’t care about the sovereignty of states, and so will powerful states when facing a clear and present danger. Authoritarianism will take over, a less democratic world order appear.

5. Democracies cannot be defended in a democratic way

Another notorious dilemma: democratic tolerance can only be defended in an intolerant way. We simply cannot differ about the democratic space to differ. Democratic rules ensure freedom, but only if everyone submits to them. This raises the question: do democracies need to be more intolerant in the coming years, to ensure a fee and open society? The current rise of oppressive groups, in and around democracies, clearly points towards a yes. And so, expect to see more ‘inevitable intolerance’ coming from democracies as a matter of self preservation. Democratic governments will have to be specific about the rules of an open and free society, and they will have to enforce these rules where needed. A process as unavoidable as it is tricky, because of the continuous risk that democracies become too specific about the rules and a source of oppression in their fight for freedom.

Pick whatever empire; it started with successful farmers (2/2)

No urban achievements without agricultural achievements. On 14 December 2012 we saw how this was true for the Egyptians and Maya. Now let’s take a look at the Greek, the Romans, the Asians and the Northern Europeans.

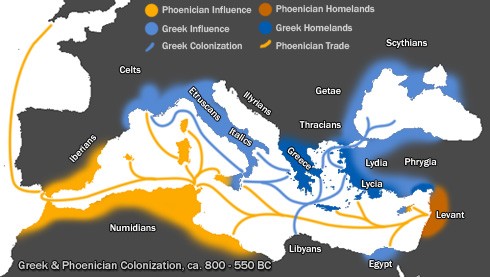

The Greek

Greece has never been blessed with a lot of fertile soil. In Ancient times, less than 20% of the land could be used for farming. So, as soon as the Greek had figured out how to follow the Phoenicians in building reliable ships (around 800 BC), they started sailing the Black and Mediterranean Sea, establishing some 500 colonies in fertile areas. This marked the beginning of a flourishing civilization with city states building a powerful culture on food that was shipped from other places.

The Romans

Like the ancient cities of Greece, there would not have a been a big and powerful Rome without a steady stream of food supplies from other parts of Europe. According to the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus, North Africa supplied Rome eight months of the year, Egypt the other four.

So, feel free to build your metropole anywhere you like, just make sure you have some friends that are able and willing to feed you on a daily basis.

The Asians

In Asia we see a pretty clear pattern: cultivate rice and empires arise. Behind the power and cultural achievements of the Gupta dynasty in India (320-535), the Tang dynasty in China (618-907) and the Silla dynasty in Korea (668-935) lies a massive investment in new rice fields. The same can be said about the powerful states of Java and Sumatra in the same period.

Northern Europeans

It wasn’t much fun being a farmer in Northern Europe before the heavy plough arrived in the Middle Ages. Until then, ploughs couldn’t plough deep enough to turn over the heavy clay soil. But the heavy plough made it possible, and around 1000 AD the land between the Loire and the Elbe had become a patchwork of grain fields. And as clay soil was more fertile than the lighter soil types of Southern Europe, this caused a major power shift from the south to the north. Professor Thomas Barnebeck Andersen of the University of Southern Denmark:

The heavy plough turned European agriculture and economy on its head. Suddenly the fields with the heavy, fatty and moist clay soils became those that gave the greatest yields.

The economy in these places improved and this sparked the growth of big cities with more people and more trade. The heavy plough started an upward spiral in new areas.

My point may be clear: no urban achievements without agricultural achievements.