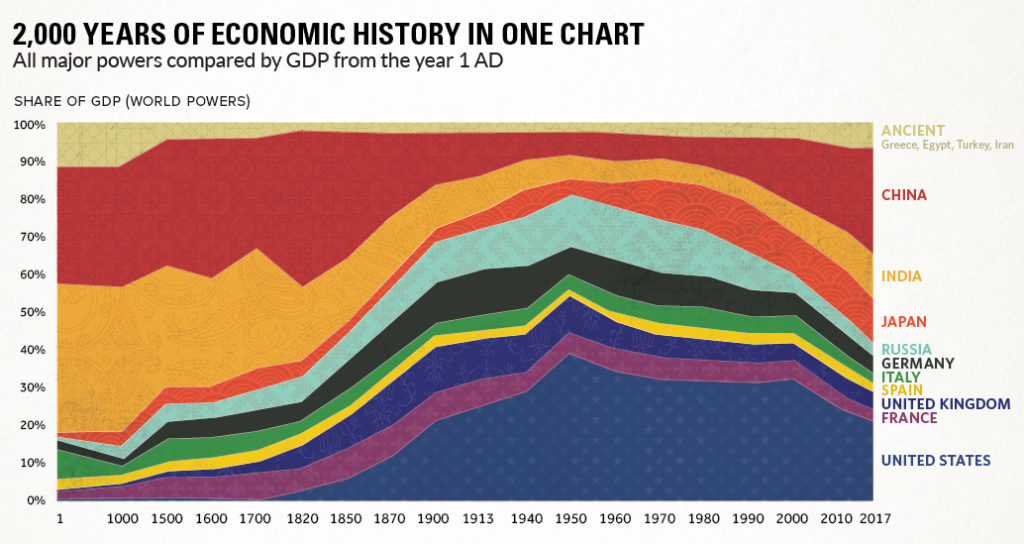

Five centuries of western domination are currently being replaced by a new world order. All the political, economic, military, cultural and ideological cards are already being reshuffled. If the Corona virus rages deep enough, it will ‘only’ catalyze this transition. In this essay, I try to briefly describe three of these major intersections in our time. Part 2: ‘Glocal’ competition / Part 1. Ideological / Part 3. Social

The world is in transition, insisting first of all on ideological reflection within societies. Let us now consider this transition from an international point of view, for there is a second issue that was already on our plate but is now becoming more pressing: how important is national self-determination in a world that gets more and more intertwined and faces more and more threats that require international coordination?

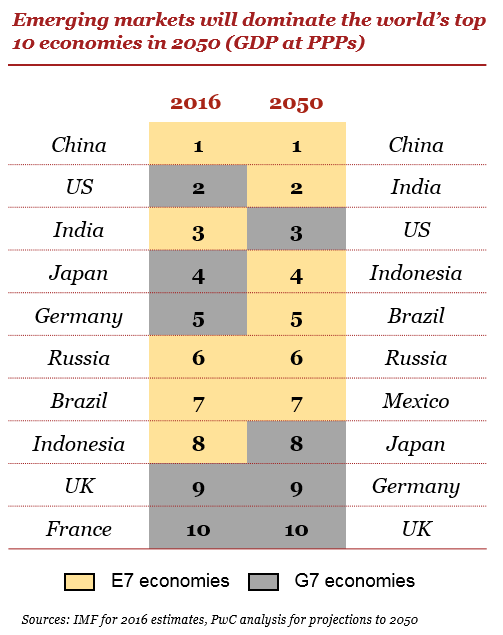

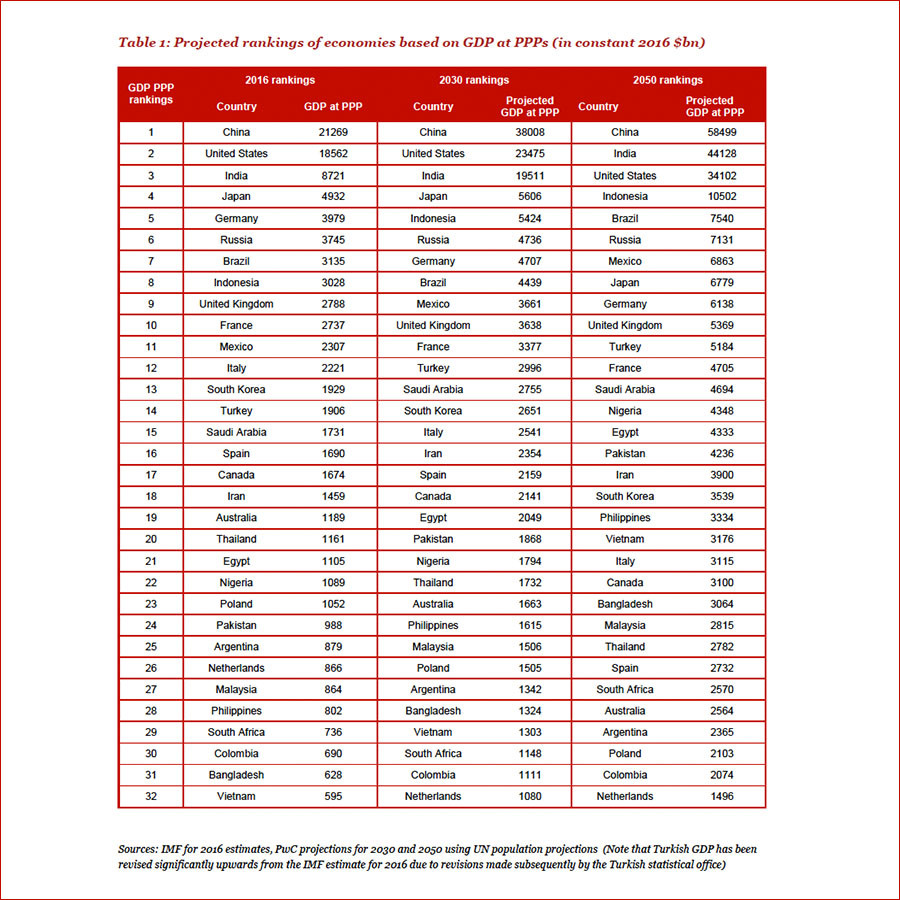

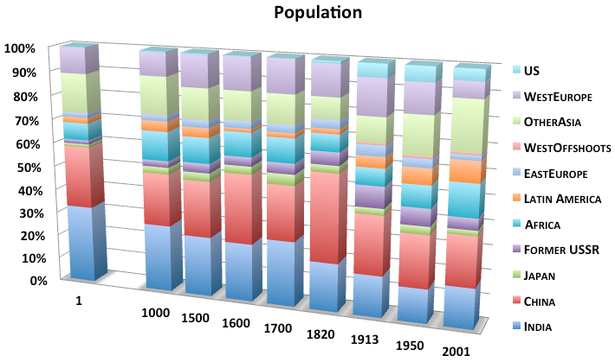

Globalisation is not exactly new. As far as we remember, people get further and further away from home, in search of new opportunities. The result is a succession of winners and losers in history: those who benefit from other nations and those who don’t. Winners gain from free movement of people, goods and services; losers prefer to shut their borders. In the past centuries the West was on the winning side, eagerly calling on their right to free trade when selling — just an example — opium to the Chinese. In our days we see the Chinese, Indians, Poles and Mexicans seizing the opportunities of free movement, and now it is the richest part of the West who responds with America First (Trump), We Want Our Country Back (UKIP) and The Netherlands Is Ours (Party for Freedom).

Behind this nostalgic nationalism and ironic protectionism lies a double motive: loss of western control makes people feel threatened not only economically but also culturally. Chinese and Russians buy western companies and football clubs; western mosques and Islamic schools are being financed with Turkish and Arabian money. Add to this the alleged islamification of Europe, and in the Netherlands the fight over Black Pete, and for some it is clear that not only western economy but also western culture needs to be defended fiercely.

In the meantime, something else is going on, something without precedent in history: never before did the whole world need to work together to get the whole planet in shape. All nations face the same climate change, nuclear risks, scarcity of water and raw materials, cyber threats, refugee movements, human trafficking, et cetera. Each of these issues requires international coordination to be dealt with in an effective way. No hacker, tsunami or human trafficker, no radioactive water leaking from a nuclear power plant, cares about national borders, trade balances or cultural heritage. In all of these cases, nationalism can only fail.

Now look at the pandemic the world is facing, in the midst of this ‘glocal’ competition. Another planetary issue is binding the nations, precisely when nationalism is on the rise. To which side will the scale tip: to international collaboration or national self-sufficiency? At the moment we see both: each country fighting the same virus as if the rest of the planet (or the EU) does not exist, and scientists working together across the globe to develop a vaccine.

The latter reveals a significant fact, something that shaped the course of Europe’s history but is easily forgotten in nationalist times: science and technology are no local affairs, but determine the fate of all humankind. Countries who shield their science and technology from other countries, may save a patent or two, but will lose the global potential of brainpower, knowledge and innovation.

What, then, to think of the economy? Will corona drive our economies away from each other or towards each other? Here, we can learn an important lesson from history. During World War I, it became painfully clear how vulnerable countries can get when global trade comes to a stop. Several countries faced a dire shortage of food, leading, for example, to a national revolt in the Netherlands. After the war, many countries tried to learn their lesson by aiming for economic self-sufficiency (autarky). This led, however, to winners and losers. Some countries were doing much better in taking care of themselves than others. After a couple of decades, three proud nations who got stuck in their own autarky policy and believed they deserved more land, resources and colonies, started World War II.

Today, we witness again the vulnerability of a globalised world. First physically, then economically. Lack of global trade is leading again to serious shortages, and again it can be tempting for (especially western) politicians to advocate for economic self-sufficiency. In some cases this will make a lot of sense, like with medical equipment and medicines or to reduce CO2 emissions. But also this new self-sufficiency will lead to winners and losers. Famines and civil wars may be the result of other countries closing their factories. And (not as dramatic but relevant for export countries): less import from a country can easily lead to less export to that country.

Another issue has moved up the agenda: when is it appropriate for a nation to defend its self-interests, and when will it only shoot itself in the foot if it does not invest in good relationships and generous collaboration with other nations?

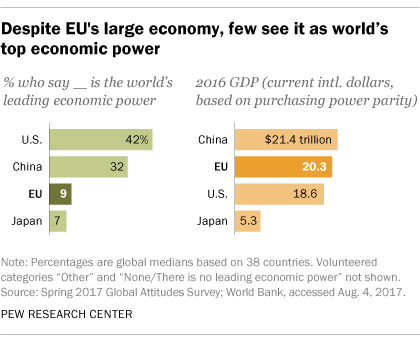

The West is losing control in the world and especially the United States and Great-Britain suffer from a ‘post-imperial stress disorder’. De world is not serving the interests of the West (so much) anymore and quite some politicians take it as a an encouragement for unfettered national self-protection. Corona can enhance this tendency, but the more self-absorbed the West becomes, the more China (and soon India) will fill the international leadership vacuum. Not only because it greatly benefits from international business partners, but also because a number of planetary issues (mentioned above) still call for international coordination. In all these cases, countries will only have it their way if they are able to mobilise sufficient allies when it gets to a vote. China is well aware of this and continues to invest in good relationships, also (and precisely) in corona time. The West is busy with further breaking down its old alliances. Corona makes us realise how much all nations are joined in one fate on a single planet. As westerners we used to have beautiful thoughts on this. Let us hope it will not take too long before we can explain to ourselves again, why we cherished liberty, equality and fraternity as universal values – not for one particular privileged nation, but for all of humankind.